“What is at stake in the complexities of “writing” are precisely “social relations.” Writing, not meaning or consciousness, moves through and animates the social text.”

-R. Dienst, p 134

Iñaki Urdanibia (Urdanibia in Vattimo et. al., 1990) and Jean Baudrillard (1985, p. 65) argue that the philosophical bases of modernity were placed in the XVII and XVIII centuries with Descartes, and the Enlightenment. Stemming from them, human sciences, as a novel and autonomous corpus of knowledge, are one of the backbones of Modernity.

Human sciences, in spite of the different tendencies and ruptures which they encase, have never been able to escape the fate of their own name by remaining very human and painfully rational. Human and rational are, probably the best two words, that describe the narrative in wich they rely. That narrative suppose a centralized and autonomous subject which is the bearer of language and owner of his own words. He is a rational subject capable of tracing the boundaries between real and fantasy, between truth and false, and between science and ideology. His rationality enables him to construct a narrative with a fixed meaning and to understand the correct meaning of the words. The concern with narrative in this “epoch of the logos” (Of Grammatology p.12) is, above all, a concern with truth. This concern has produced some specific conceptions of communication, language and narrative. In modernity the ideal-type of communication is linear. There is a clearly identified emitter (active) and a receptor (passive), language is conceived as clear and fixed (an un-interrupted relation between signifier and signified), and narrative follows a linear path determined by the author (which exist a priori of his text-speech and out of it).

May 1968 has been the consensual date selected to mark the emergence of a postmodern condition which questions all the basic assumptions in which modernity was rooted. The question of narrative is no exception. It is important to remember that, after all, post-structuralism “is at once a neo-structuralism and anti-structuralism” (Merquior, p. 194). There are present in that thought both: continuities and discontinuities in relation to structuralism. One of the cornerstones of structuralism is Saussure’s synchronic linguistics with the difference between the components of the sign: signifier and signified. Saussure’s linguistics emphasize the signified over the signifier. On the other hand, I will argue, that one of the shared aspects of post-structuralism in which it differ from structuralism is Lacan’s point of view in which the signified is no longer privileged. For Lacan the signified depends in a reading of the signifier, and not on the signifier itself. It is truth that Derrida differs from Lacan’s privilege of the signifier, since for Derrida they are both interchangeable, but he definitely agrees, and base his work, on the rejection of saussurean’s emphasis on the signified. Regarding this, Spivack states that on “Grammatology Derrida cautions us that, when we teach ourselves to reject the notion of the primacy of the signified -of meaning over word- we should not satisfy our longing for transcendence by giving primacy to the signifier -word over meaning. And, Derrida feels that Lacan might have perpetrated precisely this” (Of Grammatology p. lxiv).

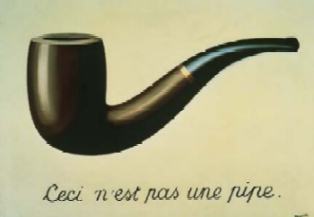

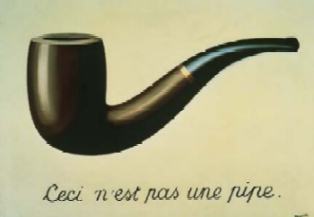

This is one of the characteristic of post-structuralism regarding language, that readings of the same signifier produce different signifieds. That is the polysemy of language. The reading of a text is as important as the text itself when giving meaning to it. The text no longer possess a fixed and unique meaning. That is one of the basic concepts of post-modern theories of narrative. Clearly influenced by french post-structuralist thought, post-modern theories of narrative put into question many notions of modern narrative. Speaking about the death of the author and the “death of the civilization of the book”, among other, this theories look forward non-logocentric conceptions of narrative and textuality. This is a reclaim for the polysemy of language. Narrative is conceive as a non lineal, open, floating bunch of signifiers grouped together, ironically, by play and force.

As we mentioned before, human science’s relation with the logocentric narrative of modernity is of a symbiotic kind by both being different sides of the same dice. Critics of modernity, better to say of that which was the project of modernity, and to its narrative are, in one way or the other, also critics of the human sciences. This critique has been introduced in the diverse and sometimes arid terrains of the human sciences. Seidman's and Clough's arguments exemplify how this critique has been introduced in the terrain of sociology.

Seidman put forward a critique to the rational discourse of science characterized by sets of binomially opposed dualities: “science superseding myth, truth overpowering fiction, freedom triumphing over bondage” (Seidman cited in Clough, p. 3). He calls for the replacement of that discourse by the configuration of “postmodern narratives” on the realm of the social sciences. In her response to Seidman, Clough argues that the argument about narrative, which Seidman deployed, ignored the question of “narrative as a form of writing” (Clough p.3). Content and form cannot be taken as separate pieces of narrative. For Clough putting into question the narrative of modernity on the social sciences is also a questioning of specific forms of writing. By the same token, the configuration of "postmodern narratives" should entail the configuration of new writing forms or practices. She put special attention to experiments in that direction done by some authors. She theorize of how their experimental forms of writing undermine the hegemonic narratives of the social sciences by opening the text to what she calls “the network imagination of telecommunications.” For her, tracing the parallels and relations between late of century communication technologies and those explorations on the form of writing is something fundamental: “I want to propose that the possibility of recent writing experiments in sociology has been conditioned by the intersection of the postmodern critique of the social sciences and telecommunications” (Clough p.3).

However, what can be said about how those telecommunications have provided for new technologies of writing? In the same direction that Clough argues that the form of writing should be taken into account when addressing the question of narrative, I believe that the question of the technology of writing should be taken also into account. My concern is the medium of textual production . The importance of the medium of production of the text lies in the fact that “The medium cannot be a transparent and homogenous operation outside of effects of writing, for all media are writings” (Dienst, p. 133). The transition from paper-hand to paper-machine as the paradigmatic technology of writing can be considered a transition into early modernity. By the same token, the image-machine (of hypertext) can be understood as a transition to the paradigmatic technology of writing of the postmodern condition.

Some Remarks About Post-Modernity